Fact Friday 348 - John Schenck, Revisited

Happy Friday!

If you've been following our Fact Friday blog posts over the past few months and weeks, then you know that we're just enthralled with all things related to John Schenck. I mean, what a life of accomplishment! Our good friends over at the Charlotte Museum of History contributed our first piece on his life in "Fact Friday 331 - Path of Portraits - John Schenck" and a more recent contribution, "Fact Friday 347 - Lydia Schenck, Charlotte's First Black Librarian," focused on John's sister-in-law, was provided by one of our newest supporters, Jeffrey Begeal, Chairperson for Social Studies and IB/AP Teacher at Harding University High School (my alma mater). This week's post will provide more context around John's life and some of his experiences.

---

John Thomas Schenck 1829 -1894,

Charlotte Politician and Community Leader

The lack of a detailed biography on John Thomas Schenck perhaps suffered from the historic notion that Reconstruction was a ‘noble failure’ and not a period Americans should study or reflect upon to any great extent. This perspective belied the fact that there was ample material on John Thomas Schenck, much of which demonstrated his capacity as a successful and influential man in Charlotte. His public work began shortly after the Civil War and lasted almost to the conclusion of the 19th Century. The obituary published by The Charlotte Observer on March 31, 1894, provided a fairly accurate tribute to the memory of John Thomas Schenck. It offered personal information and accolades that can be researched further and verified by historians. As with any obituary, the recollection of someone’s life does have certain biases and perspectives that favor the memory of the deceased. The first minor flaw would be the obituary’s claim that Schenck was 70 years of age at his death. The historical record argues against this claim. His internment at the Piedmont Cemetery in Charlotte, in the Colored People’s section, recorded his dates as 1829 to 1894. The funeral was most likely arranged by his wife, Paulina Linsday Schenck, who would know her husband’s life span. Also, in the 1850 and 1860 US Federal Census Slave Schedules for Cleveland County, NC, there were matches for a male slave that could reflect John’s existence among the slaves of Henry Schecnk, 1802 -1882. Considering that Henry Schenck and one of his plantation slaves, Jane, were John’s parents, these documents make this identification even more likely. The obituary’s claims of John’s young life have strong resonance in supporting his public career.

Because he was the son of the master and a slave, John, as a Mulatto, was not treated like a Black slave. John was taught to read and write, something that was illegal in NC for a slave to do. John was taught carpentry skills, which would be useful during his travels and contribute towards his ability to purchase his wife, and would help him survive the first years of Reconstruction in his work with the Freedmen’s Bureau in Charlotte. Henry obviously trusted his son as he allowed him to buy time and to travel with the promise to return. It was likely, though not mentioned in the obituary, that John did carpentry work on one of the Lindsay plantations in York County, SC and met Paulina. The Schenck family history was that John paid a Lindsay plantation owner $1,500 in gold for Paulina, money he had earned from his skills as a carpenter. When John traveled to Europe and Latin America was not stated in his obituary, but it may have been in the 1850s and before he purchased Paulina. Passenger shipping records did not record John’s voyages, but it was likely he was a crew member for hire and not a passenger. What was not mentioned about these years, were the skills John used to build his savings, and the anti-slavery perspectives he was exposed to. He returned to his father’s plantation before the outbreak of the Civil War. When NC seceded from the Union in 1861, Henry sent John to work on the breastworks at Wilmington. Did Henry do it out of patriotism for his State? Did Henry persuade John that the money he earned he would get to keep a portion of? No historical records revealed John joining Confederate forces, thus it was likely he was sent to Wilmington as hired labor. In the obituary, John used this opportunity to desert the work he was entrusted to do and to join the Union forces.

What John did during the Civil War, again, has no historical records for confirmation. Historians only have the obituary’s story. How John got from Wilmington to Tennessee to join General George Stoneman’s Cavalry was a mystery. If John joined the Union forces, it was not supported by troop records from the National Archives. That situation in itself did not mean it did not happen. John could have volunteered his services to a calvary officer and was not on the official troop rolls. Stoneman’s forces were scheduled to raid Virginia and western North Carolina, the latter an area John had a vested interested in. For instance, when in March 1865, one brigade from Stoneman’s forces, under the command of Brigadier General William J. Palmer, led Union forces against Lincolnton in Lincoln County NC, it's likely that they entered Cleveland County where the Henry Schenck plantation was located. If John was with the Palmer forces, there was no record, but if he was, his knowledge of the area, his willingness to serve, and his steadfast character may have been influential in persuading Union forces to spare from destruction his father’s property. A comparison for the 1860 and 1870 US Federal Census records showed no substantial loss in Henry Schenck’s personal estate wealth, thus historians can conclude that his property was spared during the Stoneman raid of March 1865. After the Civil War ended, John began his public life.

Schenck and Early Republican Politics

In the 1866 Colored Convention in Raleigh and in the Freemen’s Bureau Records were the first places John’s name appeared in the historical record. Thus, from the end of the Civil War in April 1865 to 1866, John had moved to Charlotte and was engaged with local politics that affected the conditions of the Freedmen. Why did John not return to Cleveland County to help his father on the Schenck plantation? The historical record did not offer an explanation, but there were conjectures that could offer a scenario. John had deserted during the war, a time he clearly broke from his father’s intentions. When he joined Stoneman’s forces, John used his influence to spare his father’s property. But all was not well on the Schenck plantation. Henry had married his first wife, Sarah Ramsaur in 1829, the same year he had fathered John with his slave Jane. Sarah had died October 23, 1874. Henry had married a second wife, Lucinda P., who died in 1892 and was buried next to him in the New Bethel Baptist Cemetery in Lawndale, Cleveland County, NC. Did either of these women want John on the Schenck plantation as he grew into manhood and must have resembled his father? As a carpenter, John had worked off the plantation and was allowed to earn his own money. Was his absence encouraged by Henry’s wives? President Jefferson had freed his children with Sally Heming and sent them away from their home. As the constant flow of visitors to Monticello and the relatives who lived there must have noticed the resemblance of these children to the former Presidents, it became an awkward situation for the social mores of that time. Thus, John’s not returning to the Schenck plantation and his relocating to Charlotte where he could find work and explore his political convictions might have been the best solution for the Schenck family after the war. What was known from this decision was that John became an advocate for the Freedmen community and a local Republican politician dedicated to improving conditions in his city and State.

Although John did not attend the 1865 Colored Convention in Raleigh, he did attend the 1866 Colored Convention. This second Convention had the focus on education for the Freedmen. This was an area that John would champion both for his own family and his Charlotte community. At the Convention, John was appointed to the Executive Board from Mecklenburg County. As a member of the Republican Party, John was a fairly conservative and pragmatic politician. He represented the 2nd Ward, which would later be referred to as Brooklyn, as Alderman with four terms in office. The Aldermen Meeting minutes mentioned in the Charlotte newspapers revealed John to be a competent local leader and an able administrator for city affairs. On September 10, 1867, Schenck was elected as a Republican delegate from Mecklenburg to the State Convention. On Oct 8,1867 Schenck was elected on the State Committee for the Platform and Resolutions. Keeping to his conciliatory tone, he voted against the confiscation of property of Confederate supporters and sympathizers. Back in Charlotte on November 12, 1867 Schenck was appointed inspector of elections for his Charlotte precinct, 2nd Ward. In August 1868, John was the first Freedman added to the Charlotte police force. For the 1868 State Constitutional Convention, John did not serve as a delegate, but the resulting Constitution, crafted by Black and White delegates, he approved, and he urged the electorate to vote for its passage. In 1870, Schenck won his first term as Alderman in Charlotte for the 2nd Ward. He served as a delegate to a Republican Convention in Salisbury in August of that year but revealed his independence when he voted against the proposed gubernatorial candidate. In May 1871, Schenck was re-elected as Alderman. He was also appointed the mail agent for the A T & O Railroad. In April 1872, John was elected as a delegate to State Convention of the Republican Party, He spoke at Statesville, and he invited white men into the Republican Party who favored Black equality.

Schenck and the Freedmen’s Bureau

John’s connection to the Freemen’s Bureau benefited his family and members of the Black Community in Charlotte. The first interaction was with the Freedmen’s Bureau hospital in Charlotte in 1867. Several children of the Schenck family suffered from an outbreak of smallpox and needed medical care. One child was Lydia Schenck, a sister of Paulina and adopted into the family. Other children recorded were Alice and Amie Schenck. These later two could have been children of John and Paulina, as in Paulina’s obituary in 1933, it mentioned two daughters who had died before her and had been school teachers in Charlotte.

Then there was the controversial plan to help move destitute Freedmen from Mecklenburg County to Mississippi in order to find work. John was advised by Freedmen Bureau agents in Charlotte, most likely A. W. Shafeer and H. M. Lazalle, who served in 1867. The story itself did not appear in the Freedmen Bureau Records but later in the Charlotte newspapers. (1877 ) In this instance, Schenck was accused by A. Johnson and J. B. Lynch of the Colonialization Association of sending Blacks to Mississippi as a way to enrich himself. Schenck published a detailed rebuttal outlining the event and his intentions as well as the part he played.

John wrote a letter in 1868 to the Freedmen’s Bureau advocating the establishment of a branch of the Freedmen Bank in Charlotte. John did carpentry work to prepare the selected site, and he was paid for his work.

Schenck and his business affairs

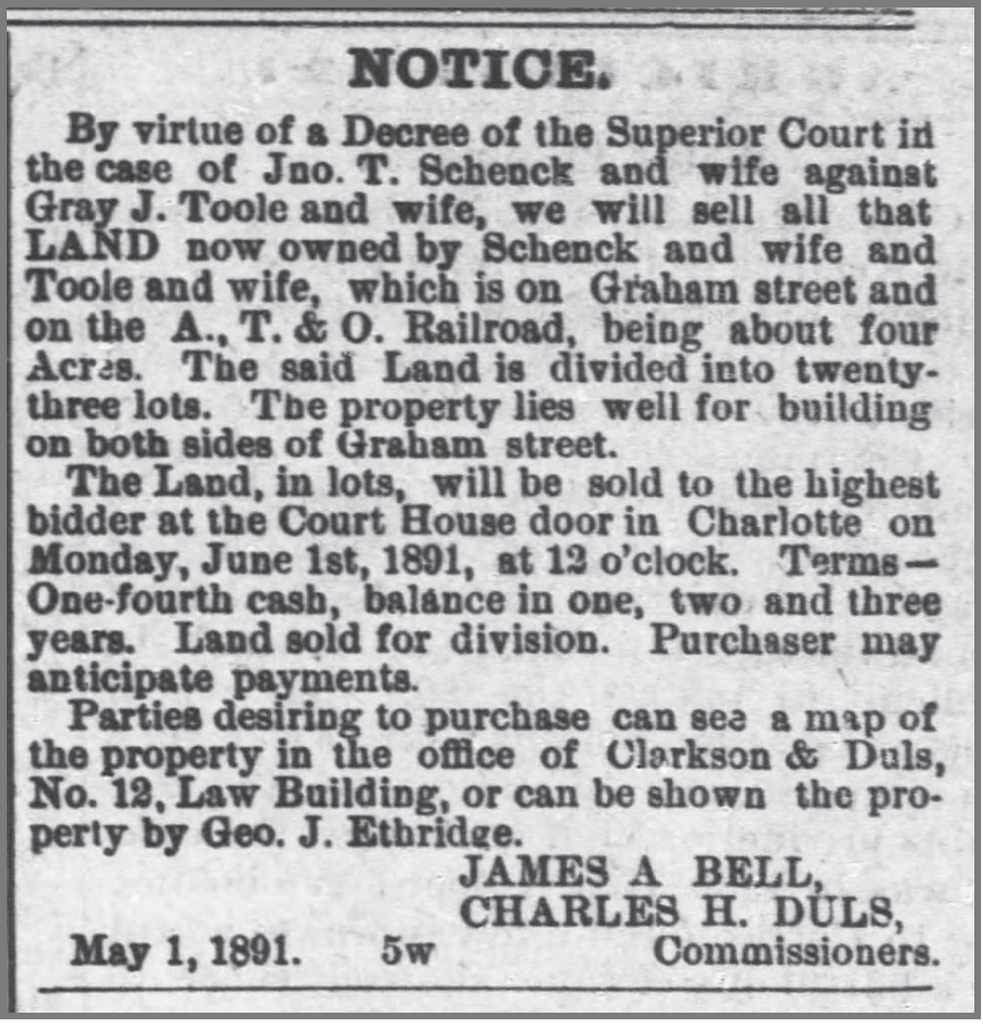

The business affairs that John Schenck conducted were diverse as he had to work to support his family, and by doing so created generational wealth. John and Paulina as purchasers of lots and land in Charlotte did not start until 1870 and according to the Mecklenburg County Record of Deeds, John had been involved in various projects, or ‘wire pulling’ as his obituary noted. His first success was a saloon owner. Schecnk had created a business firm with two other Black partners, the barber, Ferry Morehead, and Milton Davis. In 1874, they were involved in disputes with city officials by selling liquor on Sundays within the city limits. John Ozment, another saloon owner and rival of Schenck, had lodged the complaint. The Mayor’s court found in favor of Schenck but the rivalries continued. By 1877, Schenck went so far as to move two small houses that served as his saloons outside the city limits to avoid further controversy. In 1881, Schenck also fought against the prohibition law of the Temperance Movement in Charlotte. Rental properties and a grocery store were also his business concerns. He formed another partnership with Gray Toole, Schenck and Toole, in the buying and selling of city lots in Charlotte.

In the late 1880s and early 1890’s, Schenck had several difficulties with some of his properties going up for sheriff’s sales for back taxes. There were several law suits that Scheck was involved in during this same period. Despite these controversies and setbacks, Schenck was a successful businessman. His wife Paulina was left with an estate where she could live at their home until her death in 1933. Schenck had created generational wealth around properties on South Mint Street in Charlotte. Although the Bank of America Stadium and Route 277 in Charlotte have built over much of what Schenck and other Freedmen created, there is still room on the cleared lot where Paulina’s last home was to erect a historical marker on South Mint Street in their honor.

Schenck in Post Reconstruction Republican Politics

When Reconstruction ended in 1870 in North Carolina, John Schenck remained active in Republican politics. He was elected Alderman two more times in the 1880s. The minutes of Aldermen’s meetings, published in Charlotte newspapers, demonstrated that Schenck was a competent and experienced elected official. His only disappointment was that Black Republicans were no longer put forward for State offices during elections. State contests after Reconstruction were reserved for White Republicans in North Carolina. Schenck himself was thwarted from a federal appointment to serve as an official at the Mint in Charlotte (Charlotte Observer July 4, 1880). Schenck’s statement from the Republican Convention in Raleigh: For twenty years working for the Republican Party with all my brain and with all my strength and with all my money, underscored his frustration. 1882 was the biggest split of Black and White Republicans reported in the Charlotte newspapers from October to November of 1882, where Schenck threatened to leave the party. He and the White leaders of the party reconciled, and they invited him to speak at the Raleigh Republican Convention. In 1884 was Schenck’s fullest frustration with the Republican Party in NC. Schenck spoke at many Republican party meetings in the State, and in several instances bemoaned the fact that Blacks could not gain party support to run for State offices. On several occasions, most notably on October 16, 1888, he threatened to throw his support to the Third-Party ticket, Republican Blacks in NC, who wanted to participate in the electoral process. In local politics Schenck secured the $2000 bond for S J Caldwell, Black, elected as Constable. Schenck, though, wanted to run for the State legislature, but the White Republican Executive Committee denied his candidacy. City Alderman was the only elected post he would secure. When he moved to the 3rd Ward, he was elected as Inspector of Elections on October 23, 1891, but not to the Alderman seat. The discrimination of the Jim Crow era against Blacks thwarted his plans in post Reconstruction politics, but he remained loyal to the party and supported Republican candidates for President. In February 1894, Schenck gave his last speech arguing for the rightful place of Black Republicans in NC.

The character of a remarkable man

John Schenck was a caring family man and one who was concerned with his community. He and his wife Paulina adopted children from Paulina’s family when they moved to Charlotte while they were struggling to establish themselves financially in Charlotte. Schenck understood the destitution of many members of the Freedmen community. When posters announced workers were needed in Mississippi, Schenck not only arranged for the Charlotte Freedmen’s travels, he also accompanied them. Schenck took his duties as a new citizen seriously, and throughout the decades he exercised his rights in the courts to settle his legal disputes. From 1872 to 1874, the Charlotte newspapers followed the Stolen Tobacco Case, which threatened to implicate Schenck and destroy his public reputation. Schenck defended himself ably against the charges where he proved he was framed. He had the case moved to Superior Court to exercise his right to a trial by jury and was acquitted. In June 1879, Schenck was hit by a train and had to have his arm amputated. He sued in court and won $1300 in compensation. He encouraged and supported Black civic organizations and the founding of Black churches in Charlotte. He had worked at the Biddle Institute (Johnson C Smith University) with his carpentry skills. In 1882, the Colored Neptune Fire Department of Charlotte hosted two out of town Black Fire Departments, and Schenck served as master of ceremonies. In 1885, an abandoned baby was left on his front porch. He and Paulina cared for the child as one of their own. His gray filly, which had pulled his sulky around town for years, died in February 1893, and he noted the animal’s faithfulness. When a young couple was walking hand in hand to the magistrate’s office, Schenck, along with a small crowd, followed them suspecting the couple wanted to register for a marriage license. When the clerk said the fee was $2, the couple looked chagrin. Schenck stepped in, passed the hat, and he contributed himself until the fee was raised and the certificate issued. Schenck had educated all his adopted nieces and nephews. His only natural born son, John Schenck, Jr. (1869-1962) went to college and law school with his father’s financial support. He became an Assistant District Attorney in Boston who dealt with immigration cases. Like many of the Freedmen who moved to Charlotte after the Civil War, John Thomas Schenck had to create a life where he could build his fortune and reputation. He contributed to his community as he rose and remained a strong and dedicated leader in the face of adversity.

Until next week!

Source:

Jeffrey Begeal

Chairperson for Social Studies

AP/IB History Teacher

Harding University High School

Charlotte, NC 28208

---

Email chris@704shop.com if you have interesting Charlotte facts you’d like to share or just to provide feedback!

“History is not the past, it is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.” - James Baldwin